In a monumental environmental triumph, the lower Klamath River now runs unimpeded for the first time in more than a century, granting salmon a clear path to their ancestral spawning grounds. Kiewit Infrastructure West Co., utilizing a progressive design-build contract model, successfully dismantled four hydroelectric dams, restoring 35 miles of river in Oregon and California to their natural state. This marks the completion of the largest dam removal project ever undertaken in the Western Hemisphere.

Turning the tide: A collaborative feat

Built between 1911 and 1962, the four dams along the Klamath River had severely impacted fish populations and water quality. What was once the third-largest salmon-producing river on the Pacific West Coast saw its salmon population plummet due to increased water temperatures and high algae content. Native American tribes downstream, who relied on the river’s fish populations, were particularly affected, leading to a series of legal challenges beginning in 2006. These efforts culminated in the Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement and the formation of the Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC) in 2016. The KRRC was funded with $450 million from California water bonds and PacifiCorp customer surcharges.

After six years of progressive design-build work, the ambitious joint effort with Knight Piésold, engineer of record, was finalized in October 2024. Extensive permitting from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and various federal, state and local agencies took four years, while construction was accomplished in just two.

Most of the work was self-performed by Kiewit, requiring meticulous access planning and approaches, including the use of temporary bridges, cofferdams and track-line excavators to rappel equipment down steep slopes. Other operations required to complete the project included dredging in front of the Copco No. 1 tunnel adit using Flexifloat barges and cranes; drilling and blasting of both rock and concrete; hazardous abatement; and electrical and mechanical removals.

One river, four dams, countless challenges

“What made the project special was its size and magnitude,” said Project Manager Dan Petersen. “We ran it as three individual project sites across two states, but they all had to be integrated and coordinated.”

The dams each presented unique challenges.

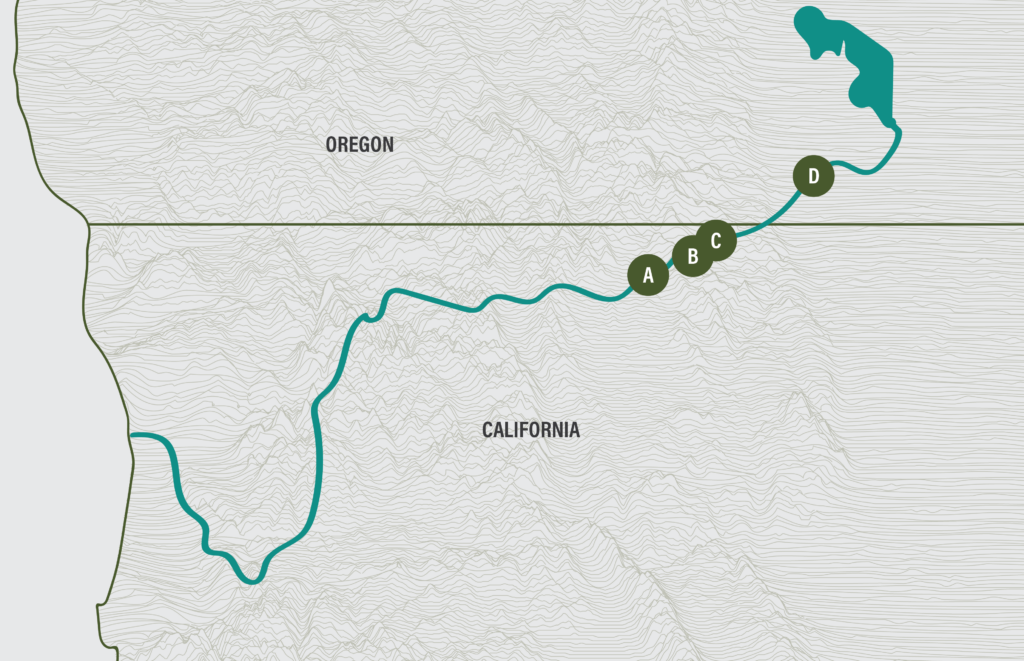

A. Iron Gate Dam (California): The 160-foot-tall earthen embankment dam posed significant safety risks, as the emergency spillway was non-functional during its removal. With over 1 million cubic yards of embankment to excavate, seasonal timing and upstream flow control were crucial.

B. Copco No. 2 (California): Also built in the early 1900s, this dam was removed “in the dry” by balancing reservoirs weekly and working within dry outage periods.

C. Copco No. 1 (California): Built in the early 1900s, this concrete dam contained steel railroad rails for reinforcement instead of rebar. Removing it required mining a 10-foot-diameter, 90-foot-long tunnel through the base of the 100-foot-thick dam and blasting out the remaining plug to drain the reservoir.

D. J.C. Boyle Dam (Oregon): The 2-mile-long concrete conveyance canal along the Klamath River canyon led to two 10-foot diameter penstocks, dropping water 400 vertical feet to the powerhouse, required specialized winch-supported gear.

“There were a lot of risks and not a lot of past projects with dam demolition to learn from,” said Petersen. “We focused on fundamentals — detailed work plans, engaged ‘play of the day’ meetings, and a constant focus to improve something daily.”

“Every aspect of this project required custom solutions,” added Project Sponsor Nick Drury. “It wasn’t just a matter of moving dirt; we had to navigate through regulatory requirements and safety protocols while working in rugged, remote locations.”

Balancing nature, deadlines and risks

Managing the reservoirs while maintaining downstream water flow was one of the team’s greatest challenges. They had to align work with salmon migration and spawning seasons, as even small delays could have pushed the project back by an entire year. Staying connected was crucial. The job required significant hydraulic analysis and planning during both preconstruction and construction. It was essential to align planned flow releases from upstream dams to remove dams within the safest windows, maximize sediment flushing, and provide for contingency plans if the project faced a high-flow event.

“The tight windows around salmon migration meant there was zero room for error,” Drury said. “The timing had to be perfect, and the entire team knew that one slip-up could delay the project by a full year.”

The team coordinated progress across the three sites through daily “play of the day” calls and manager meetings, ensuring alignment of efforts. Safety and environmental staff, along with the construction manager, were shared across all sites to keep resources efficient and consistent.

“We were trying to balance four reservoirs at one time — giving us access to work while keeping the right amount of water going downstream and protecting against a 100-year flood,” said Drury.

Bridging teams, building trust

Both the operation of multiple project sites and the remote nature of those sites presented specific challenges. Kiewit was able to implement an arrangement to conquer both.

Approximately 75 percent of the team lived on-site, with Kiewit establishing two temporary camps that housed 54 and 20 RVs, respectively. These camps featured laundry facilities, exercise equipment and a temporary cellphone tower to keep workers connected with their families. Petersen explained the importance of this unconventional arrangement, as well as how it shifted the team’s mentality about the work.

“It was important because we were two hours away from any towns.” He said, “You’re not doing the nine-to-five grind. You come back to the camp and you’re still talking about the work and what we’re going to do tomorrow.”

Having the team live on-site wasn’t just a logistical necessity — it became a bonding experience that proved to be an important part of fostering collaboration, said Drury. Petersen agreed, “Every day, we had the different sites present in front of each other and talk about their work. The jobs were competitive with each other, took pride in their projects and it really showed. That extra drive and energy to do well just made everything easier,” he said.

One of the most challenging aspects of demolishing the JC Boyle earthen dam in Oregon was the removal of double penstocks, each about 10 feet in diameter. Water was kept level for about two miles, then dropped down the steep mountain in penstocks to drive power. The team brought in track line excavators to repel equipment down the steep slopes.

A river reborn

Infrastructure projects of this size are notorious for delays and budget overruns. Despite the size and complexity of the project, it was completed both ahead of schedule and on budget. Laura Hazlett, chief operations officer and chief financial officer for KRRC, emphasized the team’s quick problem-solving ability and Kiewit’s strong execution.

“This is the largest watershed project done in the U.S., and from the very beginning, a lot of people were concerned about all of the what-ifs. It was a risky project, but I always felt like we were in very good hands.”

Hazlett said the team was able to put together prompt solutions to anything that came up, and Kiewit was able to implement those solutions almost instantly.

“I very much appreciate the opportunistic nature of how they work. I think, at the end of the day, that led to the success of the project,” she said. “That leads to good results. I couldn’t have hoped for anything better,” she said. “I think Kiewit was wonderful to work with. I’d recommend them. I’d work with them again in a heartbeat.”

With the dams removed, the Klamath River is poised to regain its status as a thriving habitat for salmon and other species. The project’s completion is not only a significant environmental milestone but also a precedent for future large-scale restoration efforts.