How Kiewit tackles water quality challenges in Los Angeles

Most beachgoers in the Santa Monica Bay area have never heard of Ballona Creek, but they’ve likely seen its impact. This nearly nine-mile channel winds through Culver City, carrying stormwater runoff, trash and other pollutants into the ocean. But that’s soon changing.

To tackle the problem at its source, the Los Angeles Bureau of Engineering and LA Sanitation and Environment partnered with Kiewit Infrastructure West Co. to reduce pollution and improve water quality before it reaches the bay.

The Ballona Creek and Sepulveda Channel Low-Flow Treatment Facilities project is a major step forward. This bid-build project aims to reduce bacteria like E. coli to protect marine life, public health and the environment.

“Once operational, these facilities will immediately enhance water quality in the surrounding areas, significantly benefiting recreational activities,” said Nicholas Miner, one of the project managers. “Additionally, they will provide the city with a valuable new source of reclaimed water.”

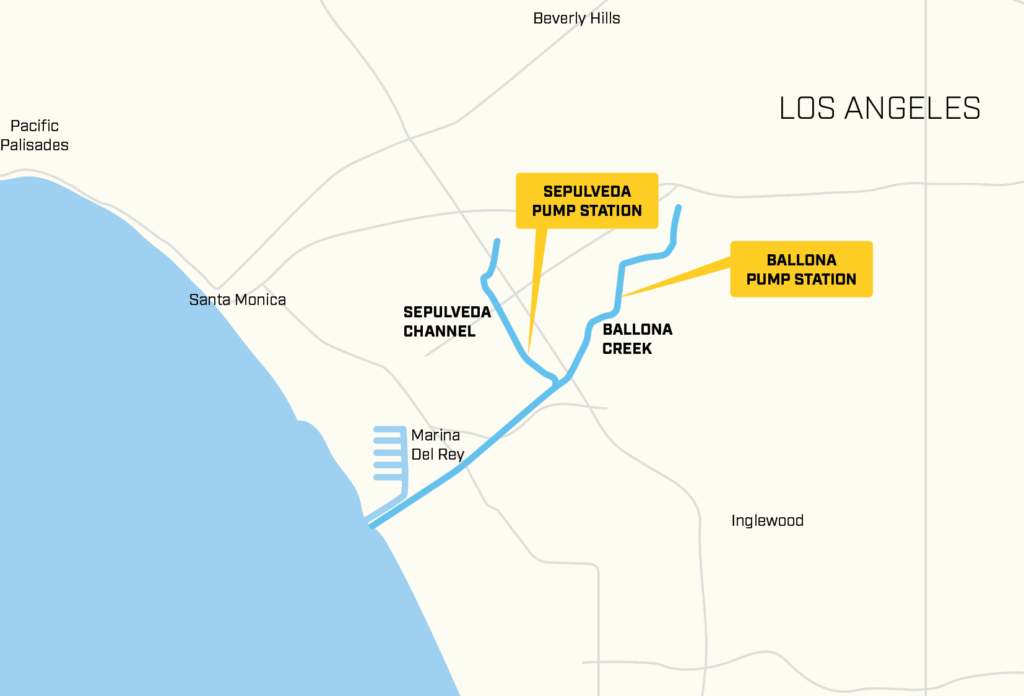

The dual-site infrastructure project includes two treatment facilities: one at Ballona Creek and one at Sepulveda Channel, about seven miles apart. Each is designed to capture runoff and stormwater, treat it using ozone disinfection technology and return the treated water back into the creek or divert it to the Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant for additional treatment or reuse.

Kiewit was tasked with demolishing the existing structures with foundation walls 30 feet underground. Kiewit was also responsible for constructing two new pump stations, diversion structures — underground systems that redirect dry-season runoff toward treatment — and overflow systems to manage heavy rainfall. The project also includes maintenance buildings, ozone-disinfection equipment and full-system integration and testing before handover.

Portions of the diversion structures had to be built during the dry season (April–October) because they sit within the water channel, requiring specific permits and dry conditions. But even with planning, the team encountered unexpected site conditions.

Overcoming unexpected challenges

During preconstruction, groundwater levels were significantly higher than the geotechnical report indicated. Kiewit worked with the city to revise the plans through RFIs (requests for information). With the design updated to prevent excavation flooding, the city granted a schedule extension. The project remains on track for February 2026 completion.

The Ballona Creek and Sepulveda Channel Low-Flow Treatment Facilities span two sites, seven miles apart in southwest Los Angeles. The Ballona Pump Station is near Ballona Creek, and the Sepulveda Pump Station is near the Sepulveda Channel. With the project being so close to the Southern California coast, the nearest beach is only a 15-minute drive from both sites.

A culture of collaboration

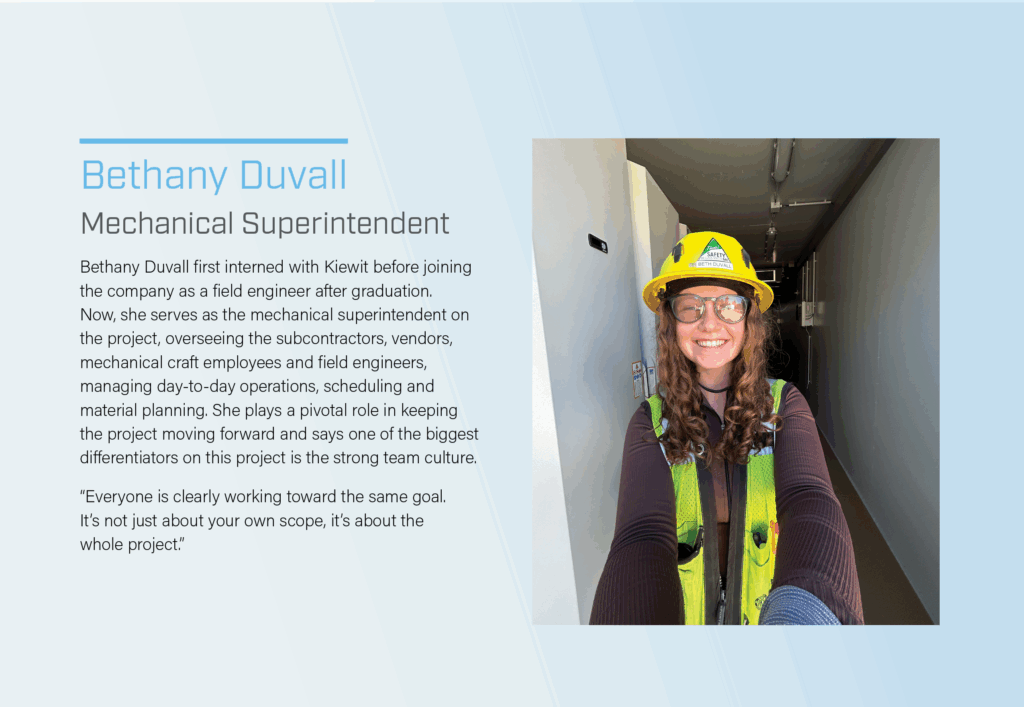

Everyone on the project agrees: The team’s dedication and collaboration have kept the project on time and on budget.

“From apprentices on site all the way up to the project sponsor, no one was afraid to get their hands dirty to help each other, especially outside their role,” said Miner. “The team collaboration on the project is worth recognizing.”

With a peak team of 10 staff and 30 craft employees, coordination was essential. Many were early in their careers, and Miner emphasized the importance of sticking to Kiewit’s fundamentals to maintain a safety-first culture. To date, the project has achieved more than 100,000 safe working hours.

“At the end of the day, what I’m proudest of is the people we’ve developed,” said Miner. “We had a very young team, so one of my jobs was making sure I gave them the tools to develop and prepared them to grow into leadership roles.”

When Miner transitioned to a new project, Project Engineer Anthony Orozco stepped into the project manager role, his first at Kiewit.

“As a leader on the project, it was important that I understood everyone’s capabilities, worked with them to make sure they reached their full potential and communicated the clear vision for the rest of the project,” said Orozco. “During my transition, I took a look at the big picture. I had the right people in the right places, so I focused on strengthening communication within the team so we could ultimately deliver a quality project to the client.”

The engineering behind 50-foot walls

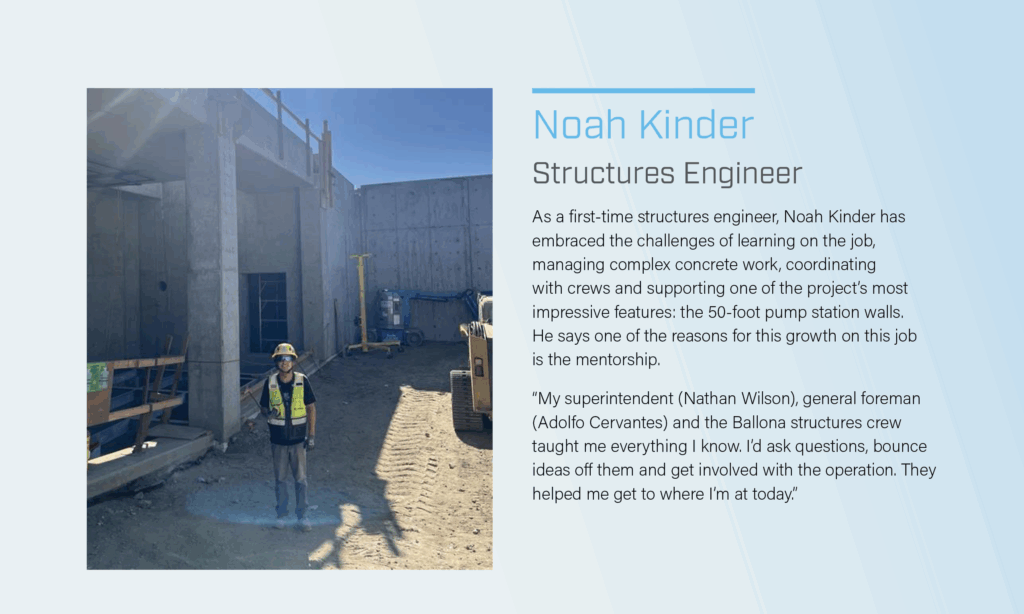

As part of the structural backbone of the underground pump stations, Kiewit constructed massive 50-foot concrete walls which were among the project’s biggest challenges. In summer 2024, the Ballona crew formed, poured and stripped the pump station walls under budget thanks to detailed planning.

Early involvement of the foremen, collaboration with subject matter experts, engineering analysis and pour sequencing were key. The team designed custom concrete molds and coordinated closely with the rebar subcontractor.

The walls were placed in 6-foot-per-hour lifts using a concrete pump. Tremie hoppers, funnel-shaped devices connected to rubber elephant trunk hoses, ensured accurate and controlled placement of concrete in deep or hard-to-reach areas. Mid-wall “pour windows” allowed crews to monitor and consolidate the concrete during the operation.

“The 50-foot concrete walls were a huge milestone,” said Noah Kinder, structures engineer. “The successful execution was because of our team. It was an exciting process to see played out.”

It’s no small feat constructing 50-foot concrete walls. This progress photo at Ballona Creek, taken at about 15 percent completion, shows two corners of the building being poured as crews erected the next two wall sections. Maintaining the design pour rate was vital to prevent formwork failure.

What happens after the pump?

The Ballona and Sepulveda facilities use ozone disinfection, a technology that breaks down pollutants using ozone gas created on-site from chilled oxygen.

Here’s how it works: Water is gravity-fed into a wet well — a collection chamber that temporarily holds incoming water — then pumped into the treatment system. Ozone is injected to oxidize the water and destroy bacteria, pesticides and organic matter. The pipe diameter increases to slow water flow and maximize ozone contact time. Once treated, the water is returned to the creek. At the Ballona site, a bypass option allows untreated flow to be diverted directly to the Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant when needed.

At the Ballona Creek facility, pumps draw water from the wet well and distribute it through two separate flow paths. One header routes water vertically through the roof to the ozone disinfection system, while the other directs flow to the Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant via a bypass line.

The first step in constructing the pump station buildings involved preparing the foundation. Here, the pour crew places concrete for one section of the Ballona Creek building. The foundation was covered with a vapor barrier and reinforced with rebar and concrete forms, ensuring long-term stability, preventing groundwater seepage and maintaining building integrity.

Looking ahead

By early 2026, both treatment facilities will be fully operational. Startup will include system checks, equipment testing and city staff training, with Kiewit guiding the transition. Once complete, the project will mark a turning point for a waterway once known more for what it carried away than what it protected. Each gallon treated means fewer contaminants will reach Santa Monica Bay, helping ensure that the city’s beaches are cleaner, its marine ecosystems are more resilient and its residents are safer, whether they’re at work upstream or wading into the surf.