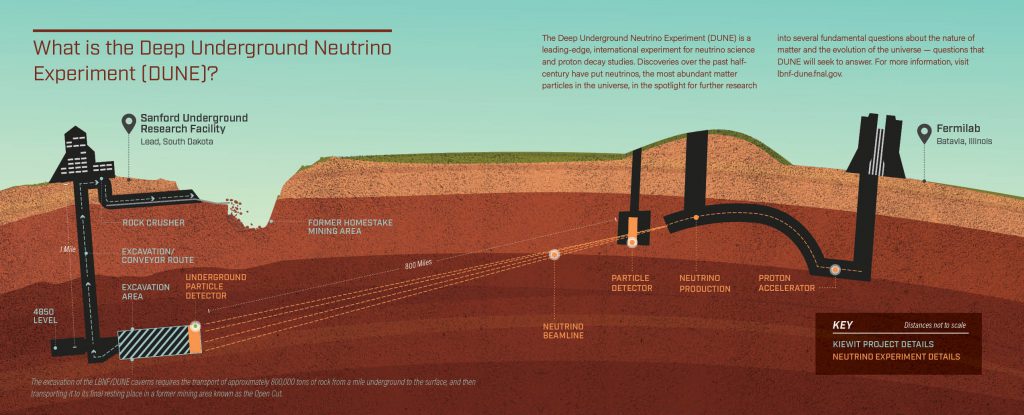

Three massive caverns nearly a mile underground. Scientific equipment that stands four stories tall. Hundreds of scientists from across the globe determined to find answers to fundamental questions about the nature of matter and the evolution of the universe. No, this is not the next blockbuster science fiction movie — it’s a project currently underway in South Dakota.

In Lead, South Dakota, a small town about 50 miles from Mt. Rushmore, construction crews are laying

the groundwork for the Long-Baseline Neutrino Facility (LBNF), which will serve as home to the

Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE) hosted by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermilab. DUNE represents the largest physics experiment

in U.S. history.

The South Dakota portion of the LBNF construction takes place at the Sanford Underground Research Facility, also called the Sanford Lab, which makes use of a former gold mine operated by the Homestake Mining Company. The mine closed in 2002 after a more than century-long run as one of the largest gold producers in the U.S.

The existing infrastructure of the mine, which includes shafts, caverns, hoists and a large open pit, is well-suited for the LBNF. However, there is still substantial rehabilitation, repair and refurbishment required to accommodate DUNE, which will involve more than 1,000 scientists and engineers from 30 countries.

The cornerstone of the project is an array of four, four-story particle detectors, each containing 17,000 tons of liquid argon, which will be located roughly a mile underground. To accommodate the detectors, approximately 800,000 tons of rock will be excavated to create three massive caverns. Before excavation can begin, however, substantial pre-excavation work was necessary.

In November 2018, Kiewit-Alberici Joint Venture (KAJV) was selected by Fermi Research Alliance LLC as the contractor for the pre-excavation work for the LBNF. Using a Construction Manager/General Contractor (CMGC) approach, KAJV was responsible for the development work of all underground infrastructure, restoration of a rock-crushing system and the construction of a skip loader and conveyor system.

A “ship in a bottle”

Before digging into construction work, KAJV invested a significant amount of time and energy into planning and coordination.

“We knew that there would be unknowns related to the underground infrastructure and condition of the mine,” said Scott Lundgren, project manager for Kiewit. “We also knew that getting construction work done was dependent on coordination with multiple stakeholders.”

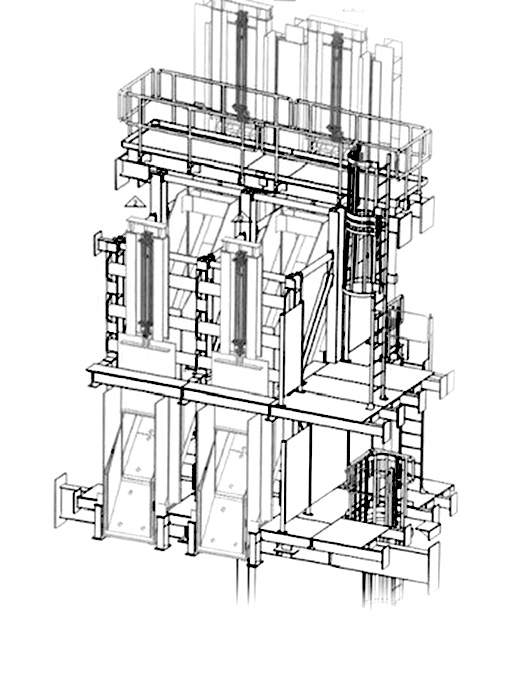

One of the first tasks was to construct the final steel set in the shaft and build a concrete sump below that, which was located at the bottom of an existing 5,000-foot shaft. Commonly referred to as the 5000 Level, the main operation was then to remove the old existing skip loader and construct the new skip loader system.

In order to access the 5000 Level and other below-grade work areas, crews relied on hoists that were operated and maintained by the South Dakota Science and Technology Authority, which manages the Sanford Underground Research Facility. The hoist system, which was originally installed in the 1930s, provided the only mode of transport to deliver equipment and materials underground.

“Our construction operations were a little bit like building a ship in a bottle,” Lundgren added. “Everything we did, everything we had to use underground or remove from underground had to go a vertical mile, and it had to fit in a 600-cubic-foot cage.”

It also required additional consideration by designers and engineers. For example, the steel pieces and beams for the new skip loader system were designed and fabricated specifically to fit into the cage. In addition, the pre-construction team ensured that material and supplies were sized, shaped and packaged accordingly.

In regard to equipment, though, items typically could not be custom-sized to fit the cage. As a result, many pieces of equipment had to be taken apart above ground and re-assembled below, which needed to be taken into account when planning construction schedules.

“We always had to be efficient with cage time,” said Joe Caggianelli, general superintendent for Kiewit. “We could only carry 6,000 pounds of material, and it took 15 to 20 minutes to get to a work station. Crews really needed to plan ahead to make sure they had everything they needed for their shift.”

Given the challenging logistics of transporting crews to work, it was an advantage to have a highly skilled, multi-disciplinary crew, many of whom had previous mining experience and were accustomed to working underground.

“For the construction of the skip loader, crews were sized to efficiently rotate between multiple tasks, including structural steel, piping, ground support and concrete,” said Aaron Heckmaster, field engineer at Kiewit. “Our crews have really excelled at everything that needed to be done.”

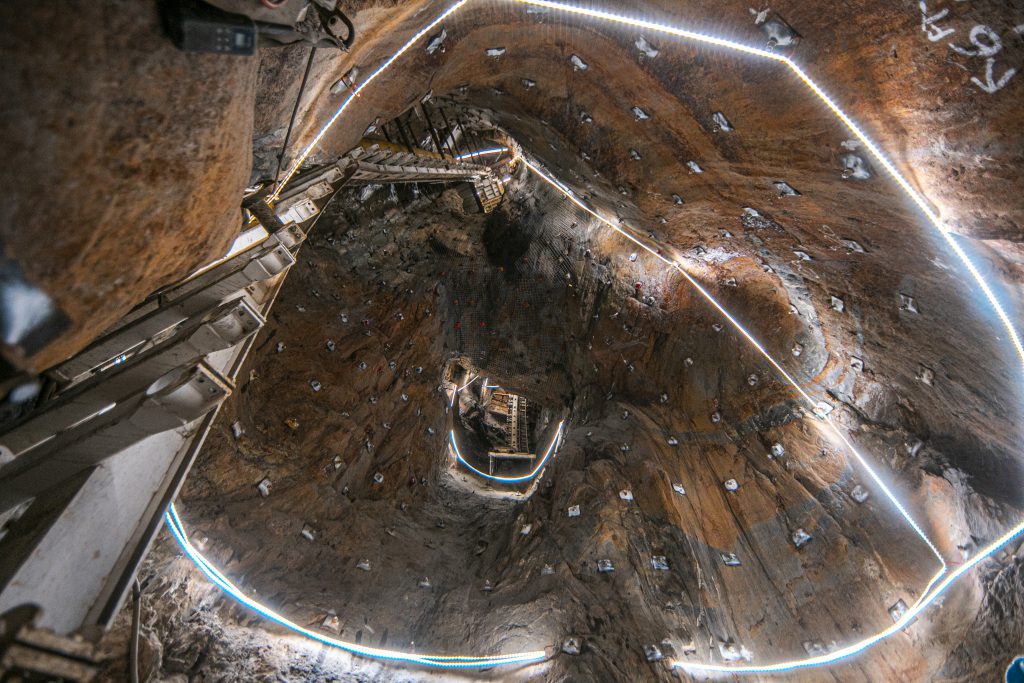

The reclaimed and rehabilitated ore pass from the historic mine works will now be used to transport excavated rock to make way for massive underground caverns. Photo credit: Matt Kapust, South Dakota Science & Technology Authority (SDSTA)

A straightforward approach

Regarding the above-grade work, which included the design and installation of a new conveyor system, the project team successfully tackled major challenges.

The new conveyor system, which spans an impressive 4,216 feet, will be used to transport excavated rock from underground caverns to the Open Cut, where the rock will be stored. The system is designed to operate 10 hours a day with the capacity to transport up to 4,000 tons of rock daily.

A portion of the system, specifically the foundations, were designed by Kiewit’s in-house engineering team.

“Working with our in-house engineering team helped maximize efficiencies,” said Ben Seling, construction manager at Kiewit. “Regardless of a few last-minute changes, they were flexible and accommodating, which ultimately prevented any design-driven construction delays.”

With limited laydown space, any deviation from the plan would have resulted in a ripple effect of delays. The installation of the bent foundation had to run according to schedule, which meant the design had to be final and accurate.

“Overall our approach was very straightforward: get it off the truck, bolt it and fly it,” added Seling.

Unfortunately, the installation of the conveyor system at the Open Cut was not as straightforward. In order to effectively deposit excavated rock, the system cantilevers over the open cut, which is nearly 1,200 feet deep at its center. Two cranes were used to complete the majority of the installation. A 450-ton crane set the first section of the conveyor at a 105-foot radius, which exceeded 90 percent of the crane’s capacity.

“There were a lot of reviews of slope stability as well as making sure that we understood how much load we could put on the rock at the edge of the cut,” Seling explained. “Additionally, an access path was cut out of the rock to accommodate the crane and this operation.”

A 250-ton hydraulic crawler crane was used as well, operating at a 38 percent grade, up a very steep access road.

“We started with a tree-covered hillside and had to pioneer the new road, which provided access for both the concrete and steel crews. It all came down to having a watertight plan,” Seling added.

Detailed planning was also crucial in installing the conveyor system over U.S. 85, a well-traveled, two-lane highway. The process began with the removal and setting of the bents, which required several nighttime highway closures.

The most visible and impressive operation involved the placement of the enclosed conveyor onto the bents. A crane lifted and set two bolted halves of an enclosed truss with a combined length of roughly 120 feet across the highway. Since the trusses already had all of the conveyor components installed, the project team was able to avoid any additional highway closures.

“The community was pretty excited the night we erected the truss over the highway,” Seling commented. “We had quite the crowd watching on their blankets and lawn chairs. The conveyor was similar to the one used for the Homestake mine so it brought back special memories for some.”

Teamwork at its best

While the next phase of the project — the excavation of approximately 800,000 tons of rock from underground caverns — is on the horizon, the project team is proud of the work that has been completed thus far.

“It’s been an awesome project,” said Heckmaster. “We are fortunate to have a team that works really well together toward our common goal. And that makes work much more enjoyable.”

For Caggianelli, who coordinates and supervises the “below the collar” work and has been with Kiewit for more 30 years, this project provided a valuable opportunity to share his knowledge and expertise with less experienced employees.

“I get a lot of satisfaction in training our young builders, whether engineers or superintendents,” he added. “Many of our employees have never worked underground like this. It may have been an eye-opening experience at first, but they were all up for the task and have done an excellent job.”

The project team engineered new equipment that could move on an incline, in a horizontal direction, within the existing ore pass.

A meticulously designed skip loader system was constructed that will eventually remove approximately 800,000 tons of excavated rock.

Six blast doors were installed to keep air pressure, air flow and blast effects away from an existing laboratory on the 4850 level.