The downtown streetcar system will soon make its debut

You’ve likely heard the saying “everything old is new again.”

That’s never been more true than for Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where the downtown area is experiencing a type of déjà vu — but with a cleaner, quieter and more efficient twist.

This fall, residents, commuters and tourists alike will have the opportunity to get a ride via a new streetcar system.

A 2.5-mile Phase 1/Lakefront starter route will begin at the Milwaukee Intermodal Station, a hub for 1.4 million bus and train passengers annually. In total, there will be 20 sheltered stops on the north-south rectangular route that covers 40 city blocks and also loops by Lake Michigan.

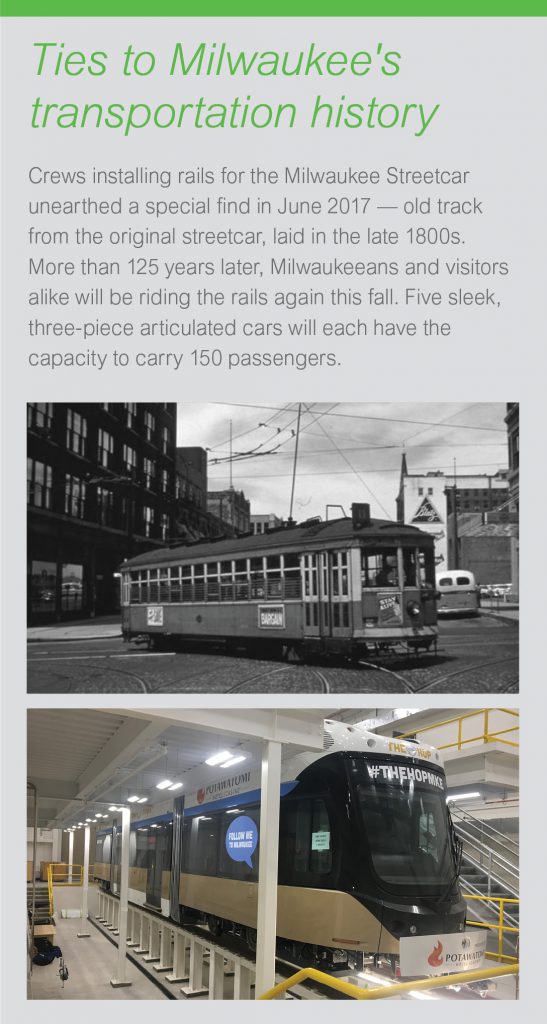

The new streetcar system is a far cry from the one that carried passengers in the mid-19th century. Back then, horse-drawn cars on rails were the conveyance. In 1890, the system transitioned to electric trolley cars.

This fall, a fleet of five sleek, modern streetcars — powered by an overhead contact system (OCS) — will take its place on the rails and share the road with cars and buses. Each streetcar has a capacity of 150 passengers and has roll-on/roll-off access for wheelchairs, strollers and bikes.

A leap of faith?

The streetcar system marks a couple of notable firsts for Kiewit Infrastructure Co., which won the $67 million CMGC (Construction Management-General Contractor) contract in 2016.

It’s Kiewit’s first-ever streetcar project and first project for the City of Milwaukee.

The scope of work includes laying over 500 pieces of 80-foot long rails, welded into long strings to construct embedded track into the existing roadway; constructing the OCS consisting of foundations, poles, wires and three substations that power the system; and building a 16,000-square-foot operations and maintenance facility to service and house the streetcars.

Entrusting Kiewit with the work may have been a leap of faith for the City of Milwaukee. But Kiewit’s reputation, along with a prolific and successful track record with light rail and other transportation projects, gave city leaders confidence.

Pedestrian control was a foremost concern during construction, particularly in areas such as the Historic Third Ward, a revitalized warehouse district filled with shops and restaurants.

Sharing the road, sharing information

“This streetcar system, by its nature, is pretty interesting,” said Project Manager Mike Ethier.

“You’re literally building a track in the middle of downtown streets. It’s not grade separated, it’s not separated by traffic, so you’re combining railroad construction and road construction all at once.”

That concept of shared use — meaning that the streetcars operate in the same lanes as other vehicles — is unique to this mode of transportation. Kiewit understood the nuances involved with that and the need to create open communication among all stakeholders.

“There are a number of access points to thousands of units, condo buildings and driveways, and to major loading docks for grocery stores and all the major downtown employers,” said Carolynn Gellings, the project’s construction manager for the City of Milwaukee.

“Building tracks through those areas is extremely challenging. Having Kiewit be upfront with their information and willing to work with all these different entities really put a good face on the project.”

Excavation through critical intersections was often performed on nights and weekends to minimize disruption to traffic.

Excavation through critical intersections was often performed on nights and weekends to minimize disruption to traffic.

Digging through history

Ethier says one of the more compelling parts of the project has involved a bit of construction archaeology.

“Working in old cities with old infrastructure, we’ve become very accustomed to working around unexpected, unknown utilities and finding things in the ground every day that are a big mystery,” he said.

And while Milwaukee doesn’t necessarily bring to mind a New York or Chicago, he said, the underground infrastructure isn’t actually that different.

As the team prepared to put in some 200 foundations to support the OCS in the sidewalk, they were frequently looking at drilling through old abandoned floors, ceilings and walls that had been filled in and were now part of the sidewalk. They were never quite sure what would be on the receiving end.

Basements that used to receive deliveries of coal, a parking garage on the site of an old power plant with three stories underground, and spaces now filled with dirt and rubble — all created uncertainties about what was once below.

“We got to see 100-plus-year-old buildings and then worked backward to figure out how they built them,” Ethier said. “That was an interesting technical challenge that we totally didn’t foresee, but one that was pretty unique.”

Accepting the risk

By the time the streetcar goes online this fall, Kiewit will have an estimated 75,000 craft man-hours for its self-perform work, with another 100,000 man-hours worked by subcontractors — with a total of 25 staff and hundreds of craft involved on the project.

It’s a prime example of how Kiewit has dug into a first-time endeavor, all the while bringing to bear the team’s previous experiences and bank of knowledge. And knowing that this infrastructure isn’t going away gives Ethier and others a sense of satisfaction.

“This is a great model reputation project for Kiewit and the city took a little bit of a risk by choosing us,” he said. “We’re sharing the same goal of delivering this the best possible way to show the state of Wisconsin that the city did right to go and build this system. In the big picture sense, we’ve all been working toward that.”

Gellings said the local community has a lot of respect for Kiewit because “they know their stuff.”

“They’ve got a great team. You can tell a lot of these people have worked together in the past and they’re extremely dedicated to what they do. The time they put in, the extra effort they’re willing to make to make sure the client’s needs are met — it’s really been a pleasure to work with them.”