Demo reveals new vista for Emerald City’s waterfront

One of Kiewit’s latest projects has taken down an iconic part of the city’s transportation system and restored something that’s been obscured for more than 60 years — the beautiful view of Elliott Bay.

The viaduct was such a fixture of the landscape that when it closed to traffic at 10 p.m. on Jan. 11, motorists stopped their cars to throw an impromptu retirement party.

Residents, office workers and tourists have collectively taken their limited view of the Seattle waterfront with a grain of salt.

When the main line of the State Route 99 Alaskan Way Viaduct debuted in 1953, it represented a trade-off of sorts.

The elevated highway provided a way to shuttle traffic for the growing city more efficiently.

But for those who enjoyed looking at the waterfront from their home or office, it marred the view.

Six decades later there’s good news on the horizon: The view is back.

Kiewit’s role in removing the old viaduct is a crucial part of the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) State Route 99 program that comprises 30 projects, including a two-mile-long bored tunnel under the city to replace the viaduct.

Viaduct demolition also clears a path for completion of Seattle’s waterfront development project.

Earlier this year WSDOT opened the new $2-billion, four-lane State Route 99 tunnel to traffic.

That cleared the way for demolition of the 1.4-mile-long viaduct, inevitable after the 2001 Nisqually earthquake left the aging structure seismically vulnerable.

Soon after the new tunnel opened, Kiewit dug in — literally.

With its subcontractor Ferma Corporation, the team began bridge demolition on Feb. 15.

Removal of the viaduct and its ramps is part of Kiewit’s four-scope contract, which also includes decommissioning the Battery Street Tunnel [see sidebar], constructing a new pedestrian bridge to the downtown ferry terminal, and reconfiguring and restoring nearby surface streets.

Viaduct demolition will be complete in October; the rest of the project is scheduled for completion by late 2020.

Keeping it down

Mitigating the effects of vibration, noise and dust in a congested urban area was top of mind for the team from the beginning.

“Seattle has aging infrastructure, plus or minus a hundred years old,” said Project Controls Manager Ryan Anderson.

“One of our biggest challenges was implementing solutions to ease the concerns of utilities providers and building owners.”

Some of the nearby buildings were just a few feet from the viaduct. In one case, the 1950s builders actually notched the viaduct around the building — leaving only two or three inches of clearance.

To make sure noise levels didn’t exceed those allowed by the permit WSDOT secured from the Seattle Department of Construction & Inspections, the Kiewit team placed seven noise-monitoring stations in strategic spots around the construction site.

Each station had a highly sensitive microphone set up to continually assess decibel levels in the area, said Chris Derbyshire, demolition engineer.

“If a station picked up a noise level that was over the threshold we set, it produced a recording. That recording helped us determine if it was something related to our work or something else in the area.”

Specially designed excavators with universal processor attachments were used to break down bigger portions of the bridge while the more delicate work was handled by sawcutting and picking.

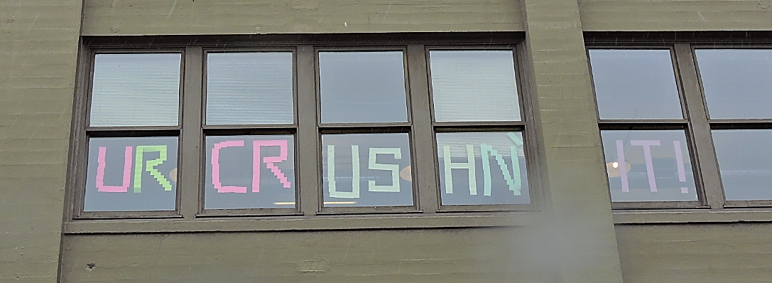

Downtown office workers and residents cheered the project along the way with window signs. “I don’t think any of us anticipated the extent to which it would elicit this sort of emotional response from Seattle,” said Alex Prentiss, Kiewit public information officer.

A soft landing

Preserving the integrity of the many older brick buildings near the bridge wasn’t the only reason the team was focused on creating effective solutions to reduce vibrations.

The location of local utilities directly underneath the viaduct — in particular, two 115-kilovolt power lines — was a primary concern.

“We were told that if those were disrupted in any way, the effects might be felt all the way up to Vancouver, (nearly 150 miles north),” Derbyshire said.

That was in addition to the sensitive location of some high-pressure water mains. The cast-iron sewer pipes, 20 to 36 inches in diameter, are over a century old.

If any of them ruptured, Derbyshire was told, “a sinkhole could happen in seconds.”

After significant field testing, Kiewit placed a rubble pad under the bridge. Made of crushed viaduct material, the pad provided a cushion for the debris to fall on.

The rubble pad started at about 2 feet deep and reached depths close to the city’s limit of 6 feet, further mitigating the effects of vibration as it accumulated. This pad moved continuously as demolition progressed along the viaduct.

Removing soot safely

Before filling the Battery Street Tunnel, Kiewit had to remove all potential hazardous materials in an environmentally responsible way.

To safely take off the soot accumulated by more than 50 years of vehicle exhaust, the team chose an innovative waterless system that used tiny bits of sponge to blast the hazardous soot buildup.

“It’s very light in your hand, and it’s ingrained with aluminum oxide shavings that give it its abrasiveness,” said Jimmy Vukelich, tunnel superintendent.

The sponge absorbs the material and can be reused five or six times before it gets completely saturated with hazardous soot. It’s then safely removed from the site and taken to a hazardous material disposal site.

Vukelich said the solution saved considerable time usually spent on trucking water tanks to the job site, filling them and ensuring the contaminated water is treated and pumped out properly.

These photos show just how close the viaduct was to buildings and nearby surface streets, making it more critical that the project team mitigate the effects of vibration, noise and dust.

Keeping stakeholders informed

The project impacted those who live and work in downtown Seattle, as well as tourists and even cruise ship travelers who had to embark and disembark right next to the demolition.

A priority has been keeping city and state officials, the Port of Seattle, local businesses and the public in the loop, said Public Information Officer Alex Prentiss.

“People feel very attached to this project and now they feel that they’re a part of rebuilding Seattle’s waterfront.”

To keep stakeholders up to date, Prentiss used a variety of communication tools, from weekly site walks and bimonthly meetings with the waterfront business community, to a WSDOT web tracker tool, weekly email updates and a 24-hour hotline.

She also gave twice-a-week communications training to onsite staff and craft during their safety orientation, distributing cards with the project’s 24-hour hotline number and email address to give to anyone who stopped to ask a question or complain.

Some of the more frequent comments were from people seeking sentimental souvenirs, she said.

“WSDOT has a list of requests for signs, storm drains, the unique 2-inch square rebar and pieces of rubble. We even saw someone selling pieces of viaduct rubble on the street,” Prentiss said.

Turning the page

It’s not often that a Kiewit team is part of a project focused on bringing down a structure rather than raising one. But that’s just one piece of this experience that the team will take away as its own souvenir, said Anderson.

“In the end, we get to be part of the project that turns the page to the next chapter for Seattle’s waterfront.”

This team, along with residents, workers and visitors, has a front-row seat for what’s next.