Every morning, Shaleen Parker greets craft workers as they arrive at the Golden Triangle Polymers Plant in Orange, Texas. As the Craft Voice in Safety (CVIS) lead, this is her way of checking on their mental and emotional well-being.

“If they’re not in the right headspace, they cannot be here and work safe. If their mind is on their family back home, or a divorce, or a suicide… if that is their focus, they cannot be here safe,” Parker emphasized.

This is Parker’s fourth project at TIC — The Industrial Company, a Kiewit subsidiary — where the commitment to “Nobody Gets Hurt” is nonnegotiable. Alarming mental health statistics in the construction industry have companies like Kiewit addressing the issue head-on.

“We’re always talking about it,” Parker says of Kiewit’s mental health program, Under the Hat.

Through gate greets, toolbox talks, training or reaching out to distressed peers, the focus is clear: Construction workers will no longer suffer in silence.

Every morning, Shaleen Parker greets the job crew at the gate to ask questions and make sure everyone is in a good headspace before starting the day.

Champions of change

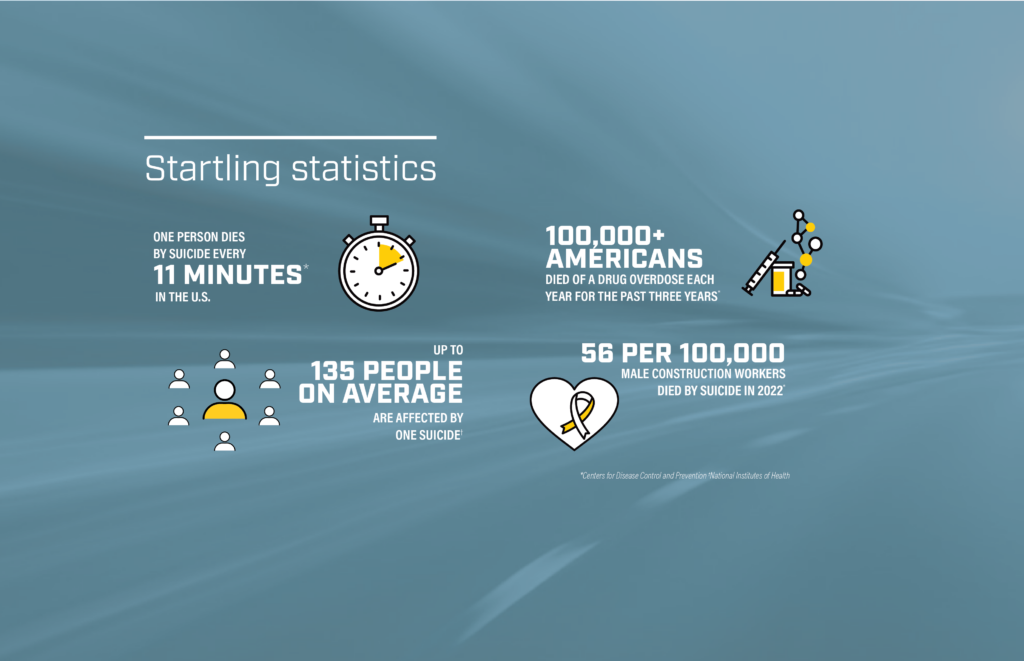

Before 2016, there wasn’t much data to uncover this public health crisis, but after a study published by The Center for Disease Control and Prevention that July, the statistics started to trickle in. As word spread, the response came in waves.

“We started the Construction Industry Alliance for Suicide Prevention in October 2016,” recalled Cal Beyer, now senior director for SAFE Project. “The most recent data for suicide in the construction industry shows 56 per 100,000 male workers died by suicide. That’s almost four times higher than the U.S. national average.”

Beyer notes that numbers are even higher for men in the mining industry, at 72 per 100,000. For perspective, construction workers are five times more likely to die by suicide than to get hurt on the job.

Before his current role, Beyer helped industry champions raise awareness of this silent crisis. SAFE Project is a national nonprofit that stands for Stop the Addiction Fatality Epidemic. He also serves on several national groups and committees, monitoring emerging data and developing responses to industry trends.

“We spend all this time on physical safety,” he pointed out. “How can we not address behavioral health — the stress, the anxiety, the substance use, suicide and opioids?”

Today, he’s connecting companies like Kiewit to help champion change. Many of them are in fact using their safety programs to open the door.

In 2021, Kiewit President and CEO Rick Lanoha linked mental health and safety in an all-company video message.

“Each of us has a responsibility,” he said. “If someone is hurting, reach out. Don’t wait for someone else to act. I expect this from you in the same way I expect you to speak up on the job if you see something unsafe.”

A few months later, Senior Vice President and Corporate Safety Head Alicia Edsen assembled a committee to streamline efforts and rebrand Kiewit’s mental health focus as Under the Hat.

“We wanted our people and their families to have easy access to the tools and services they need when times get hard. We did a lot of research on training, resources and robust mental health care benefits,” recalled Edsen.

Since the rollout of Under the Hat, Kiewit has made mental health part of the way it does business with monthly communication strategies, engaging CVIS teams and minimum signage standards. It’s also helping lead the conversation among peers.

“Kiewit has long been a leader in safety, and my expectations are that we will also lead in mental health focus and awareness,” said President and CEO Rick Lanoha. “This problem isn’t going away, and it requires everyone, in any role, to take the time and show the leadership needed to learn and help.”

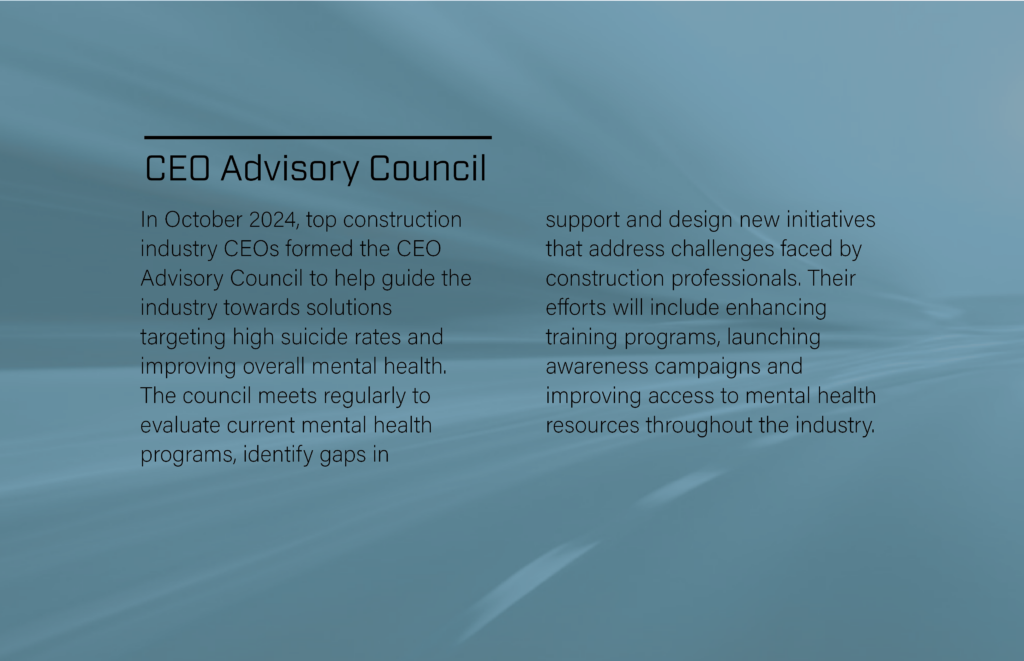

Lanoha is a founding member of the recently assembled CEO Advisory Council, a group of construction CEOs and trade union leadership focused on developing solutions to target the high suicide rates among construction workers.

“I’m encouraged to see more of our peers having real conversations about mental health. These grim statistics aren’t just numbers — they’re people — our friends, colleagues and family members. In a profession like ours, where paths often cross, we all must commit to real solutions if we want to steer industry health in the right direction,” he said.

Kiewit is also focusing on ways to build a more resilient workforce.

“Mental fitness should be part of how we care for ourselves every day, long before we reach a breaking point. It’s about acknowledging that life is hard, and we need to learn how to care for ourselves and each other through all of it,” Edsen added.

Sundt Construction has also been moving in the same direction since 2021.

“Prior to that, we often heard, ‘Leave your feelings at the gate,’” said Patricia Mason, who recruits, retains and develops craft at Sundt Construction. “Being a woman in the field, you don’t want to be seen as emotional, so I bought into that culture.”

Mason knew it was time for change. When Sundt Vice President-Corporate Director of Health, Safety and Environmental Paul Levin called for volunteers to attend the Construction Working Minds Train the Trainer Certification in 2022, Mason and Project Controls Manager Jessica Beyer stepped forward.

“That was really the pinnacle of what started,” said Jessica Beyer. “We left knowing all the statistics and understanding the raw magnitude of what our industry was facing. In our overwhelmed state, it was hard to figure out what to do next.”

The pair went from job site to job site giving mental health talks, hoping to influence a more open dialogue. In 2023, she lost a family friend, a fellow construction worker, to suicide.

“That’s when I said, ‘We really need to figure stuff out.’”

Mental Health First Aid

Jessica Beyer and Patricia Mason learned about an eight-hour Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) course through the National Council of Mental Wellbeing, received instructor certification and then began encouraging enrollment in the course. Mental Health First Aid might sound intimidating, but Jessica Beyer said MHFA relieved some of the pressure to always know the answers by having a basis of training before engaging in peer-to-peer support.

“When you complete first aid CPR, are you a doctor? No. Are you a surgeon? Absolutely not. Are you a good Samaritan? Absolutely. This is the same process,” explained Jessica Beyer.

Sundt aims to have two individuals trained in MHFA on every job site and a corporate craft trainer to provide the course in Spanish. This strategy, along with developing pre-job checklists, is part of their Emergency Action Plan.

Mason says it’s working. “While there is often still a reluctance to start these conversations, once people participate in a mental health first aid training, you find gratitude that they have been given the experience, permission to be vulnerable and opportunity to serve their fellow construction workers.”

They say support from superintendents and staff at all levels, up to executive teams, has been incredible.

Sundt Project Controls Manager Jessica Beyer is one of the company’s Mental Health First Aid instructors. The MHFA program’s official koala mascot is a nod to its Australian origins. Its name, ALGEE, is an acronym for Assess for risk of suicide orharm; Listen nonjudgmentally; Give reassurance and information; Encourage appropriate professional help; Encourage self-help and other support strategies.

Leading by example

Kiewit Chairman Emeritus Ken Stinson reinforced that leadership support is key.

“For years, leadership in the construction industry had very little awareness of the manifestation of mental illness,” he said.

Stinson, who retired as Kiewit’s CEO in 2005, says the shortage of practitioners, rising mental health issues among young people and the aftermath of COVID have compounded an already devastating epidemic. He now channels his philanthropic efforts through the Mental Health Innovation Foundation, recently supporting the construction of Children’s Nebraska Behavioral Health and Wellness Center in Omaha. Stinson believes that talking about mental health in the workplace comes down to values.

“I would almost guarantee that 99.9% of construction industry leadership, when asked what their most important asset was, would say our people. If that’s your most important asset and their lives are at risk — their performance, their marital stability, their family life — all these things are at risk, why wouldn’t you think about this as another threat to their health?”

Cal Beyer agrees, “Top-down leadership support is crucial, and leaders must be visible.” He calls it the “three Vs”: visible, vocal and vulnerable. “If you have those three, it becomes vertical up and down the organization. It takes away the fear of retaliation or reprisals.”

While the numbers are still discouraging, Cal Beyer says he sees this as a story of hope. “Our industry has responded. We didn’t sweep it under the carpet. We didn’t ignore it.”

He points to the construction companies that have adopted mental wellness programs, associations offering training and apprenticeship programs, union and nonunion, that are incorporating this into their curricula.

For the people like Parker, Mason and Jessica Beyer, who are leading the conversations, the proof is showing up on the front lines — in the field among the colleagues they care about.

“When you hear that a phone number you’ve shared with somebody really made a difference in their life, it’s why I love my job so much,” said Parker. “I think we’ve come so far, and I’m grateful for it because I see the difference it’s making out there with our craft and on this job site particularly.”

“I just love our people,” said Mason. “That’s why I do it. I don’t want to lose any more of them.”