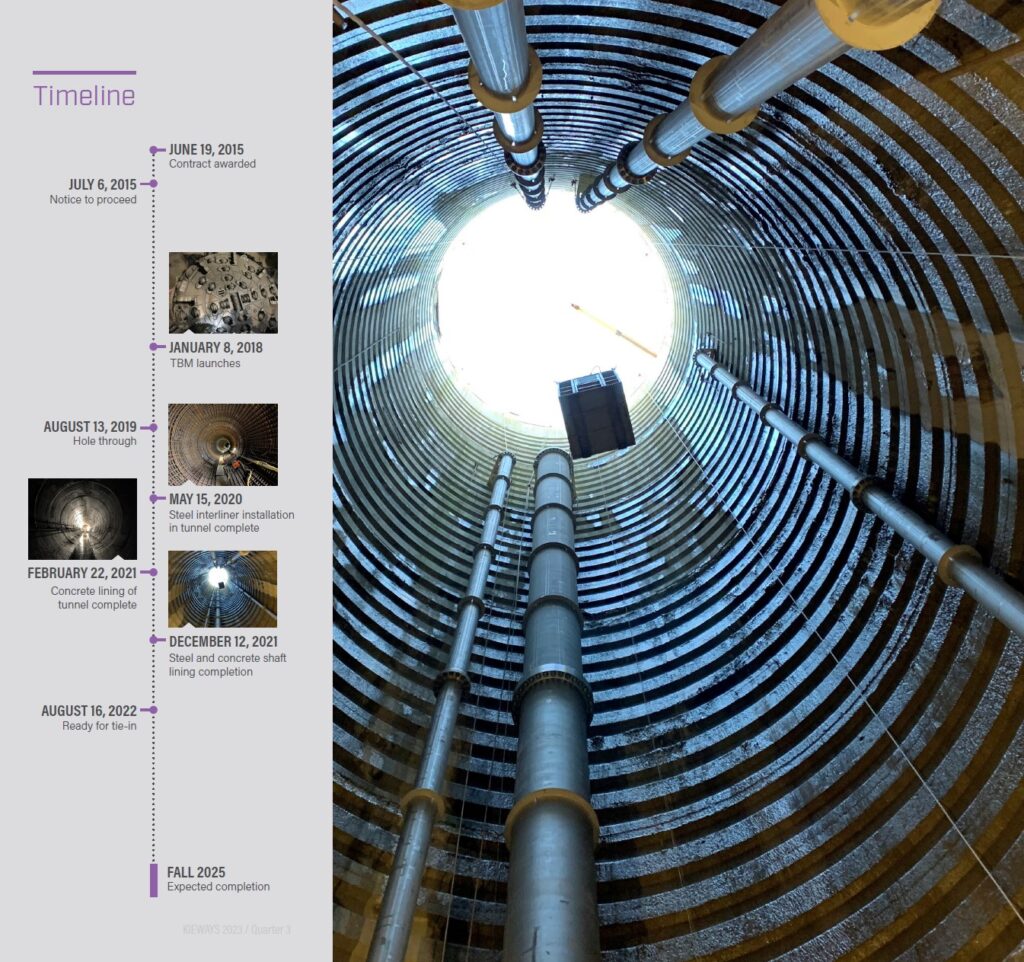

Joint venture Kiewit-Shea is scheduled to complete a 2.5-mile bypass tunnel to stop a leak in the Delaware Rondout Branch Tunnel 700 feet under the Hudson River. It’s the largest repair ever in the more than 175-year history of the New York City water supply system.

Anyone who’s enjoyed a slice of pizza or a bagel in New York City may take for granted one of its most important ingredients: water.

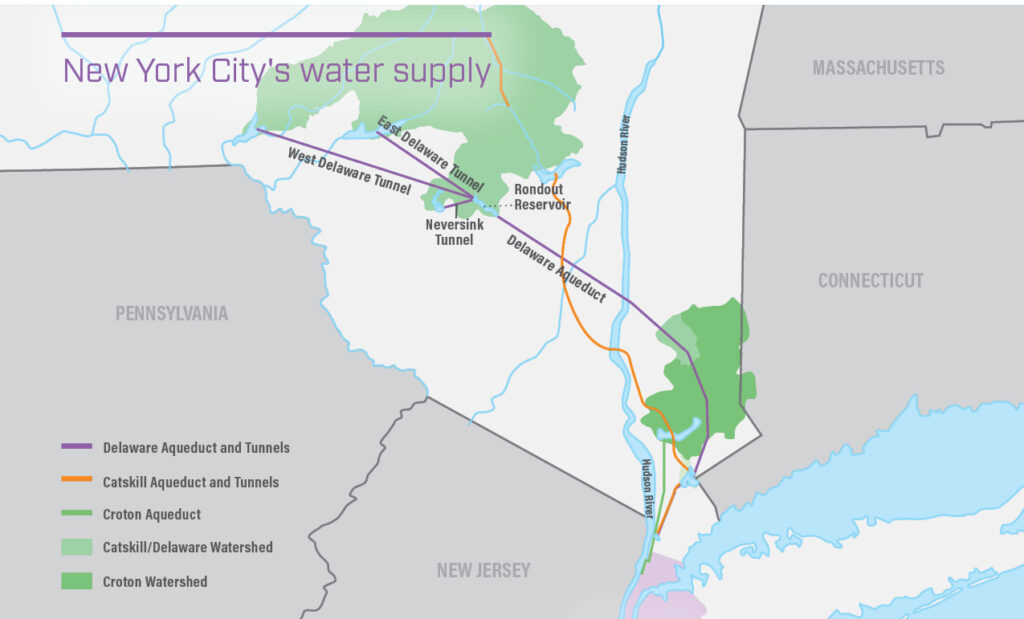

About 50% of the city’s drinking water — equaling about half a billion gallons that impact 9.6 million New Yorkers every day — comes from a watershed 125 miles north of Manhattan.

Reservoirs in the Catskills provide water from the Delaware River, carried by the Delaware Aqueduct. The longest tunnel in the world, the 85-mile-long aqueduct branches into other supply tunnels to the city and surrounding counties.

In the early 1990s, studies by the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) monitoring the aqueduct found significant leaks in one of those branch tunnels that crosses right before it reaches the Hudson River. As much as 35 million gallons of water was being lost per day.

DEP selected joint venture Kiewit-Shea to repair the leaks in the Rondout-West Branch Tunnel and construct a 2.5-mile-long bypass tunnel to tie in to the main structure and ensure the water will flow leak-free for at least a hundred years. The team began work in summer 2016.

Placing the Equipment

Working below the surface is never a simple task. On this project, the equipment had to be sent down an entry shaft about 900 feet underground and retrieved from the exit shaft about 700 feet underground.

The team elected to use a hard rock tunneling machine, which would probe out the rock up to 400 feet ahead. Lowering the assembly for the tunnel boring machine (TBM) and the concrete liner that would be placed in the tunnel required some ingenuity, said Niels Kofoed, tunnel manager.

“The deepest shaft most of us had been dealing with was maybe 100 or 150 feet for assembling a TBM, so doing the same thing through a 900-foot shaft was certainly one of the big challenges up front.”

Engineer Don Brennan developed a three-part hoisting system and assembly cradle that would carefully put together the pieces of the TBM in a confined 32-foot diameter, much like moving the pieces of a giant puzzle.

As the components were lowered into place, the team slid the pieces back and forth to accommodate them. The cutter head on the TBM itself, a 100-ton pick, was gingerly lowered in one section.

“I think that process was as impressive as what we did setting up for the actual tunneling,” said Kofoed.

Filling the Cracks

The methodology used to construct the tunnel was fairly unique, said Project Manager Grant Millener.

“We’re constructing a tunnel directly below the Hudson River. There’s infinite water inflow and the ground is fairly permeable, so we were expecting a lot of water.”

To prevent water from rushing into the tunnel as it was excavated, the team used a pre-excavation grouting method to seal off the inflow of water.

The team probe-drilled up to 400 feet ahead of the TBM. If they encountered water inflow above a preset threshold level, the team would drill and grout the holes they identified and inject grout into the rock at pressures up to 1,000 pounds per square inch.

The team had done grouting on previous projects, but this was its first time working with such a large inflow of water. Despite the challenge, the method proved very successful, said Millener.

The Perfect Mix

While the original tunnel was lined with a combination of rebar and some concrete, the new liner was built for the long haul. It boasts three layers: precast concrete, one-inch-thick steel pipe and rebar-reinforcing steel.

“It’s quite a robust lining system,” said Millener. “We started at about 21.5 feet in diameter and the final tunnel is only 14 feet in diameter.”

The outer layer, designed to support the tunnel, was set at the same time the TBM tunneled through. The other pieces were welded together, set in place and sealed. Then, the team grouted behind the pipe to the outer liner layer.

Placing the concrete for the final lining required the team to drop the concrete as much as 900 feet and then pump it.

“We pumped over a mile to the final placing,” said Matt Higgins, construction manager. “We did that for both sides of the river and it’s pretty unique to drop concrete and pump it that distance.”

Before the team placed any concrete for that final layer, they did a mockup — testing the concrete mix and the distance it needed to be pumped.

Still, adjustments were needed to get exactly the right mix, Higgins said.

“We did a bunch of testing to tweak the additives in the mix to make sure it was flowable and wouldn’t set up too fast or too slow. You’ve got to find a sweet spot where you can strip the forms as fast as you can, because it’s all cyclical. You want to be able to place the concrete, let it harden up enough and then move it ahead to do the next placement.”

At one point, he said, the team was testing every truckload that came in to get the right spread to make sure it was pumpable and would be the right mix. Sensors inside the concrete confirmed when it was the right consistency to strip the forms.

A Lasting Impact

As the team prepares to connect the bypass with the aqueduct, Kofoed said he’s most proud of the team’s ability to keep advancing the work.

“Even with all the planning that we did, we had to make a number of modifications. But the team kept moving forward and always had a positive attitude attacking the challenges.”

And while the taste of a New York City slice of pizza or bagel won’t be affected in the long term, the project will have a lasting impact in the area, Millener says.

“This is one of the world’s best water systems and we are going to provide reliable water for New York City for a hundred years. Kiewit-Shea, with its resources, was able to build the right team for the job — I’m not sure there’s any other contractor that could have tackled this challenge.”