How Kiewit achieves better, faster and cheaper projects across multiple markets

If the devil is in the design details, then the solution is in Kiewit’s divine discontent, according to Kiewit’s Chairman and CEO Bruce Grewcock.

“Our owners today, across all markets, want more realistic solutions to their problems,” Grewcock told a crowd of employee-owners at Kiewit’s 2017 Annual Meeting. “They bring us to the table and we help them take the risk out of their projects. We take out the cost and schedule blowouts that are all too common in our industry.”

How does Kiewit accomplish that? It designs projects that reflect “real constructability, real schedules and real costs,” said Grewcock. “Kiewit is a construction-driven engineering company.”

Wait, Kiewit designs projects? That might surprise anyone who recognizes the company for its reputation as a world-class builder. For those more familiar with Kiewit’s “Pleased, but not satisfied” culture, Kiewit Engineering Group — the professional design arm of the organization — is an obvious part of its evolution.

“The most common reason for cost and schedule blowouts is that during the conceptual phase of the project, things were missed,” said Dan Lumma, president of Kiewit Engineering Group.

Lumma has a tenured understanding of how those inconsistencies and missteps happen between design and construction. He’s played a lead role in Kiewit’s design capabilities in the power market since the very beginning, starting his career with Bibb and Associates, a design firm and partner acquired by Kiewit in 1998. Two years later, Kiewit was selected to engineer, procure and construct (EPC) its first marquee design project — the High Desert combined-cycle power plant in Victorville, California.

“Over the past 30 years, EPC has dominated the power market, so having an in-house engineer has been crucial,” said Lumma. “We became successful in power because we had a dedicated team that learned how to work together to the point where it’s now hard to distinguish the engineering side from the construction side when you walk on a project or go to a team meeting.”

Kevin Needham, president of Power Engineering at Kiewit, says though the company’s professional design engineers are independent from the construction side of Kiewit, being part of the same company has its advantages.

“Through repetition we become closer as a team. We get better at figuring out how to work together and how to drive costs out of our work,” said Needham, who employs approximately 1,000 designers and engineers.

In 2000, Kiewit won an EPC contract for the High Desert combined-cycle power plant — its first marquee design project since acquiring Bibb and Associates design firm two years earlier.

Kiewit's engineering approach encourages close partnerships between the design and construction teams.

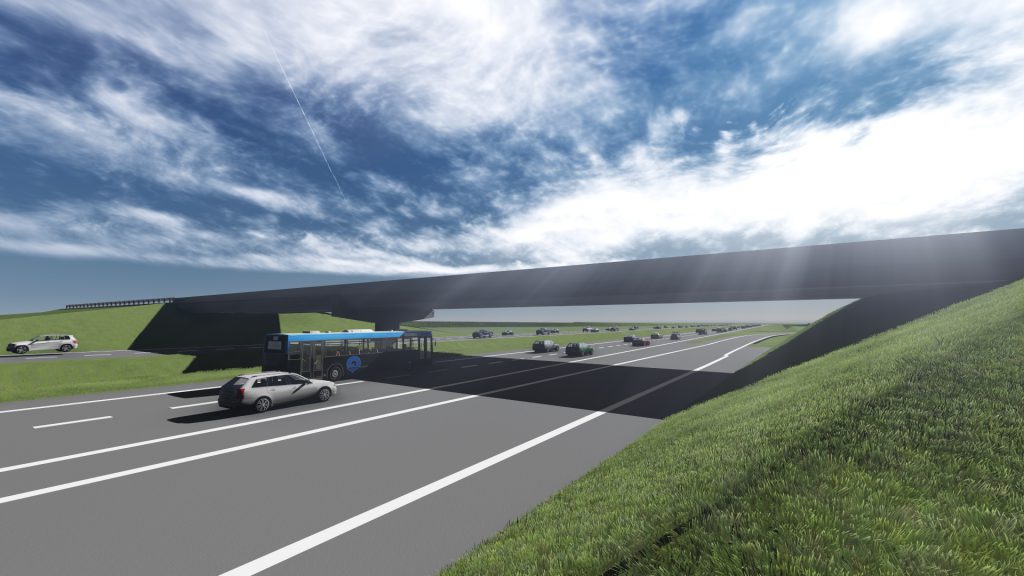

Kiewit has been selected to design and build the Warman (Highway 11) and Martensville (Highway 12) overpasses in Saskatchewan, Canada.

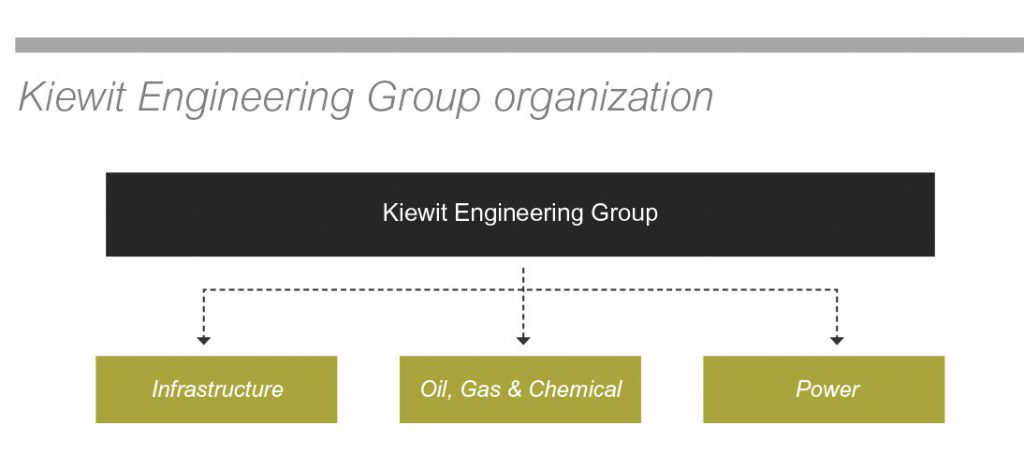

While perfecting its design capabilities in the power market, Kiewit expanded those services to two other major markets: infrastructure, led by John Donatelli, and oil, gas and chemical (OGC), led by Jay Norcross.

“We’ve always done construction engineering to support the work that the company builds, but what’s new is we’re starting to self-perform design work,” explained Donatelli. “We’re in a better position because we’re more aware of where the pain points are for construction.”

After getting the wheels in motion in 2011, Donatelli’s team is now bidding and winning transportation work across North America. Norcross, a 35-year OGC market professional, hand-picked his own team of engineers and commissioning specialists from the energy industry and is currently executing three OGC projects in Mexico. While the power, OGC and transportation teams work under one organization and may benefit from some of power’s mature processes, design isn’t a one-size-fits-all-markets business.

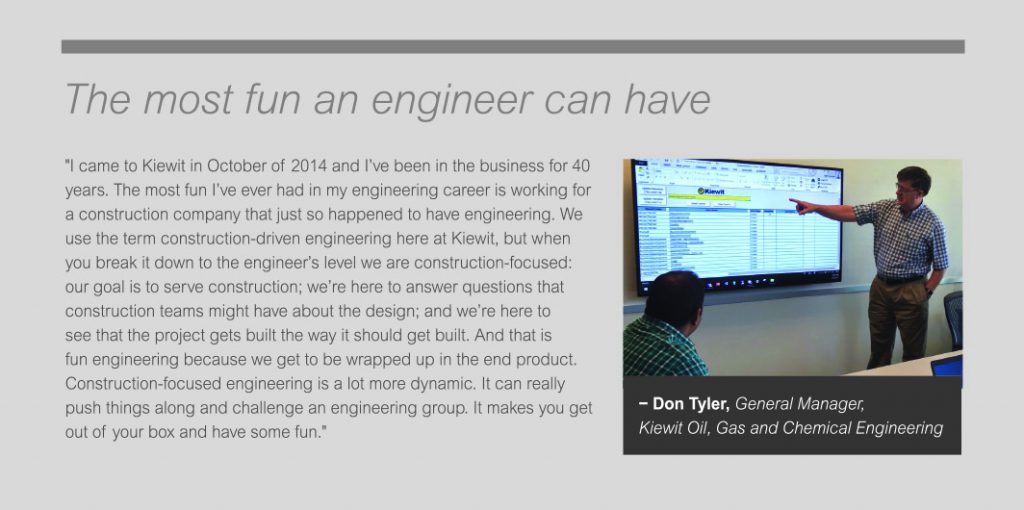

“Everything we do is about OGC,” said Norcross. “To operate in the oil and gas project delivery space for super-major oil and gas companies requires specific experience in oil and gas technologies, and in OGC project execution.”

“All three engineering teams are not identical, but the concept is the same,” said Lumma. “We have a repeatable project execution model.”

That model looks much different than a design engineering firm’s model, which is set up to bill by the man-hour. The goal of Kiewit’s model is to ensure all decisions are benefiting the client or project overall, not just what’s best for engineering, design — or even construction.

“Our business model is to be an outstanding project delivery partner,” said Lumma. “The key element is to drive costs out of the most expensive part of the project, which is typically construction in North America.”

What does that mean for Kiewit’s outside engineering partners?

“We’re still going to team with external engineers when it’s right for the project,” explained Lumma. “But now we’ll be an even better partner for them because we have that in-house experience and insight.”

Donatelli says those external engineering partners are especially important on jobs that call for a local workforce.

“We know what we bring to the table is our design-build expertise and how to perform in that contract model. What we won’t always bring is a local presence. In the infrastructure market, there are a lot of clients and there’s often a local component.”

Kiewit employees — current and prospective — also reap the benefits of the company’s engineering expertise.

Kiewit design engineers and construction teams worked together on Kentucky’s Paradise Combined Cycle Project in Drakesboro, Kentucky. Design began in Lenexa, Kansas, eight months before Kiewit started replacing Tennessee Valley’s two oldest coal-fired plants with a natural gas plant.

Whether it’s construction or design, Kiewit employees receive continuous on-the-job training and development through a variety of resources.

“One of the advantages we offer job candidates is you not only get to come here and be a design engineer,” said Needham. “You also get to see the end product of what you engineered and work on a team with your fellow constructors to make it the best possible project.”

In some cases, experiencing that project life cycle opens new doors to unexpected career paths between engineering and construction.

“There are people who spend their entire careers in a single market and others who do it for five years and say, ‘I want to try something else,’” said Norcross. “The oil, gas and chemical business is different from infrastructure and different again from power engineering in other ways. However, this diversity in execution and technologies is an advantage for Kiewit; the greater our diversity of designs and execution models, the better equipped we are to ride out economic storms, move from one area to another, keep people busy and challenge them with new opportunities,” he said.

It’s something most aspiring engineers dream of as kids, said Donatelli. “If you polled our folks who we hired from the engineering industry, I would say the number one thing that attracted them to Kiewit would be the ability to work for a company that actually builds the work they design.”

“The fact of the matter is, if we do it ourselves we can build a consistency and repeatability that you just can’t do with an outside company. This helps us become a true tier-one project delivery organization,” explained Lumma. It’s a goal clearly defined by Kiewit’s chairman and CEO during that 2017 Annual Meeting.

“We need to be a construction-first engineer, driven by real-world experience of how to actually build stuff,” said Grewcock. “And with that great Kiewit divine discontent, we put a constant emphasis on finding ways to be better, faster and cheaper.”